July 11, 2017

Click here for a PDF version of this page.

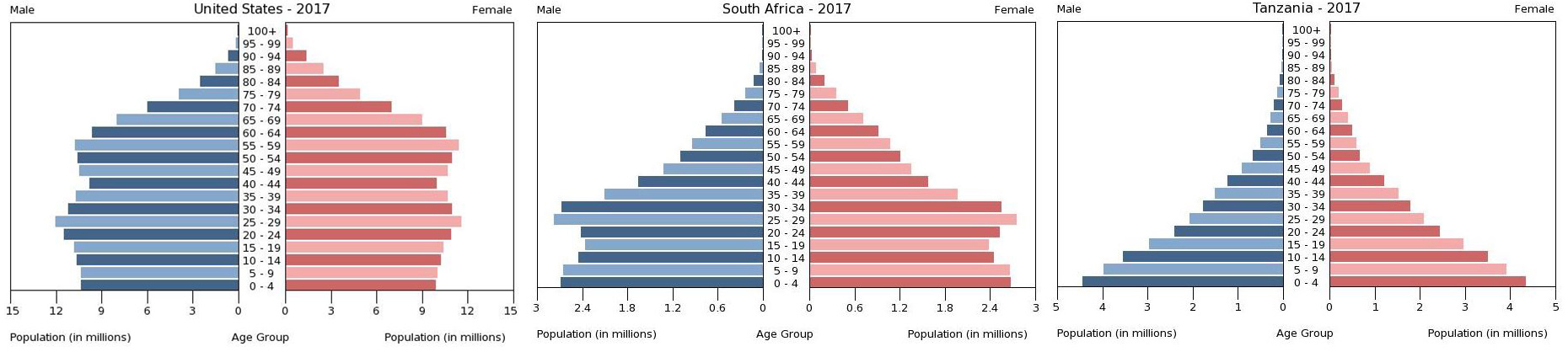

Since 1990, the global mortality rate in children under age 5 has been reduced by more than half. Thanks in part to progress against diseases such as HIV/AIDS, today there are more adolescents alive than at any point in history. As a result, demographics in developing countries around the world reflect a growing proportion of young people. In Africa alone, 41 percent of the population is under 15, with a further 19 percent between the ages of 15 and 24. This pattern is very different from developed countries such as the United States, where the proportion of young people is generally in line with older populations. The increasing proportion of young people, often referred to as the “youth bulge,” is expected to continue in Africa, with nearly 60 percent of the world’s anticipated growth by 2050 projected to occur on the continent.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

A growing youth population has incredible potential. It has the power to demand democratic forms of governance, and to serve as an economic engine that drives a country’s growth and development. At the same time, a growing youth population has significant risks. If young people are not able to find adequate employment, they put a greater strain on public services and governments, and contribute to instability and mass migration. One certainty is that a growing proportion of young people will mean major new challenges in fighting – and moving further toward ending – epidemics.

The growth in the youth population in Africa has coincided with incredible progress in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Today, there are 18.2 million people receiving treatment for HIV/AIDS, and since 2005 AIDS-related deaths have fallen 45 percent. Thanks in large part to the creation of programs such as the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), a pandemic that was once a death sentence can now be a manageable chronic disease with access to proper treatment.

However, as the population of young people across Africa continues to grow, their risk of exposure to HIV will increase. While the number of new HIV infections among children has declined 50 percent since 2010, there has been no appreciable decline in the new infection rate among adults. In children under 5, the biggest risk of HIV infection is transmission from the mother, but as an individual gets older the risks of infection become multifaceted and more complicated to address. Couple that with adolescents’ tendencies to be less risk averse, and the challenge is daunting. Adult HIV prevention programming around the world is as yet unprepared for the coming wave of young people that it will soon have to target. PEPFAR Ambassador Deborah Birx has pointed this out this challenge, suggesting that along with the success of improving survival rates for children under 5, “we didn’t adequately plan for who was going to educate those adolescents, who was going to prove healthcare for those adolescents, and who was going to provide jobs for those adolescents.”

A recent study in South Africa has shown that older men and younger girls drive the country’s epidemic. The study identified an infection cycle whereby men in their 30s infect women in their early 20s. Later in life, these women then infect their long-term partners, and the cycle of infection begins again. As the number of young women across Africa continues to grow, there is risk that we could see a dramatic increase in the number of new infections.

Therefore, scaling targeted prevention programs for a demographic group can make a real difference. Identifying the drivers of new infections as individuals get older, and targeting programs to break these cycles will be critical to preventing this risk and ultimately ending the AIDS epidemic. Delivering these lifesaving interventions at scale will require sustained financial commitments from the global community as well as increased domestic investment.

Huge progress in addressing HIV/AIDS and increased financing by governments in affected countries does not mean the U.S. can afford to invest less in fighting the diseases. Demography requires sustained commitment – by the U.S., other donor nations, as well as implementing countries.

It is common to hear people refer to our current status in the fight against AIDS as being at a tipping point in the fight against AIDS. The thing about tipping points, as former Global Fund Executive Director Dr. Mark Dybul observes, is that they can go either way. If we lean towards the future and build off the progress we have achieved, we can help young people around the world live healthy lives and realize their full potential, paving a path to significantly lower investment later. If, however, we decide to step back, we not only risk losing the potential to end the AIDS epidemic, but also risk squandering the progress that American investments have achieved. If that were to happen, we would be forced to deal with the consequences for generations to come.